Braving the Slide

An Exploration of the Dunning-Kruger Effect

“In 1995, McArthur Wheeler walked into two Pittsburgh banks and robbed them in broad daylight, with no visible attempt at disguise. He was arrested later that night, less than an hour after videotapes of him taken from surveillance cameras were broadcast on the 11 o'clock news. When police later showed him the surveillance tapes, Mr. Wheeler stared in incredulity. "But I wore the juice," he mumbled. Apparently, Mr. Wheeler was under the impression that rubbing one's face with lemon juice rendered it invisible to videotape cameras (Fuocco, 1996).”

This story of McArthur Wheeler’s hilarious attempt at criminality was ripped right from “Unskilled and Unaware of It”, the paper that established the Dunning-Kruger effect. It is named after the paper’s authors, and their chosen example effectively illustrates this article’s topic. Cognitive biases like the Dunning-Kruger effect impose themselves on our lives and thinking without us realising it. In the case of our would-be bankrobber, he was not just confident that he had succeeded in his attempt at obscuring his identity, he also could not discern competent patterns of judgement from incompetent ones. Just like many other aspects of human behaviour, cognitive biases are ubiquitous, so you will see examples of them all around and within you if only you pay enough attention.

In many ways, we’re all McArthur Wheeler. In this article I’ll be using words like “low-” and “high-performer”, but these are relative terms, and shouldn’t be taken as absolute labels for any given person. One person who is a low-performer when it comes to one task may prove to be very competent at other undertakings. The key is remembering that we can all find ourselves over assessing our own ability in a given area. None of us are above our psychology.

An attitude like Imposter Syndrome, where one feels like they don’t belong amongst their peers because they believe they lack the skill that they observe around them, is also explained through an understanding of the Dunning-Kruger effect. Explained with “Unskilled and Unaware of It”, Dunning and Kruger wrote that if one is a high-performer, incorrectly estimating one’s own competence (Imposter Syndrome) stems from a misunderstanding of others while, quite differently, if one is a low-performer (lemon juice on the face), incorrectly estimating one’s own competence stems from a misunderstanding of oneself. Imposter Syndrome surfaces, then, because we unknowingly inflate the competence of those around us, thus holding us back from embracing the confidence which may yet accompany our competence.

In his incredible book Thinking, Fast and Slow, the late, great psychologist Daniel Kahneman described how the human mind’s functioning can be approximated by imagining it as being governed by two “systems”: System 1 and System 2. System 1 is quick and emotional, and its desire is to use as little energy as possible during cognition. System 2 is slower, more methodical, and consumes more energy when activated. System 2 is typically associated with the “conscious” part of our thinking. The mental dynamic outlined by Kahneman is useful for understanding this topic because it emphasises our status as organisms who function on energy, and our brains are the hungriest part of the body. When we - oh so frequently - fall prey to cognitive biases, our System 1 is likely calling the shots to save on energy consumption.

Cognitive biases are easy to label as irrational, but we can’t simply condemn them as such and call it a day. Analyzing real-life implications, both in the environment for which we are adapted as animals and in the modern era now, reveals human decision making to be steeped in context that makes it difficult to apply “rational” and “irrational” as labels for our behaviour. For example, take the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Is it explicitly and always irrational for one to have confidence that vastly exceeds one’s competence? Not necessarily, for what if a method has “always worked”? However, if one does not adjust their thinking and behaviour despite evidence which should cause a change in confidence, that would be irrational. If a method of doing anything works well enough to achieve results for those who use that method, it may only be necessary to critically analyze that method if it does not achieve satisfactory results. Why would an organism use more energy than necessary, like by using their System 2, when the quick thinking of System 1 achieved results just fine?

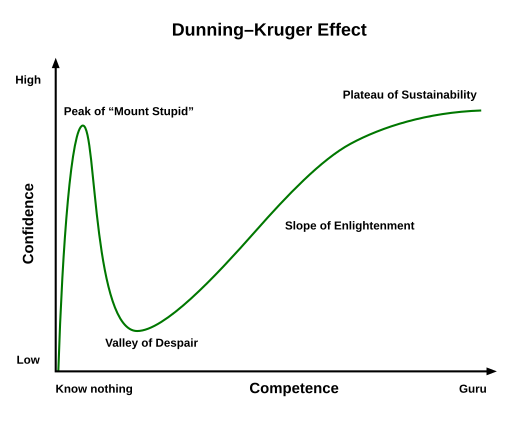

The image following this paragraph is useful for visualizing the Dunning-Kruger Effect, and it is this image which illustrates the essence of the title: Braving the Slide. The horizontal axis represents one’s actual competence and the vertical axis represents one’s confidence. The line squiggling its way across the open space of the graph is a rough approximation of one’s journey when grasping a skill or learning a concept, for example. Initially, as one gains in ability, it is common and understandable to grow in confidence, since at this stage one’s competence may not be sufficient for accurately recognizing and discriminating between varying levels of skill. The line rises drastically to represent that increase in confidence, only to fall steeply as competence increases a little more, revealing a central element of the Dunning-Kruger Effect: all it takes is a little more competence to understand just how much one has to learn, which is an intimidating and vulnerable place to be in.

Choosing to leave behind the comfort of confidence is choosing to grapple with the expanse of information and depth of competence that one does not yet have. For one perspective, here’s the brevity of Socrates: “I know that I know nothing.” Or, at greater length, Sir Isaac Newton: “To myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and … now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.” Without the humility of this perspective, without acknowledging all that one does not know, how would we go about making meaningful discoveries? Put another way, if one is confident that they have all the answers, what else is there to learn?

Though not new, echo chambers appear to have gotten worse in recent years, likely due to access to and the internal workings of social media. Echo chambers allow for a horrific feedback loop, where those with high confidence reassure themselves of their own beliefs because they are surrounded by those who think just like them. This is without even accounting for bad actors within these spaces: people who prey on others and maliciously spread misinformation to further an agenda. People lingering in echo chambers are saved from the trouble of having to use the energy-intensive System 2 and thus don’t experience the discomfort of not knowing. Seeing an echo chamber for what it is and leaving it is a decision analogous to the overall theme of this article.

Braving the Slide is risking discomfort for the prize of a better understanding. Too often do we plant our flags at the peak of Mount Stupid, allowing our confidence to inhibit our decision making and preventing us from even recognizing that our judgement has been affected. This phenomenon is known as the Double Curse of the Dunning-Kruger effect, where not only are the incompetent poor performers, but they also are unable to accurately distinguish between good and bad performance, further impeding growth. It’s illustrated well in “Unskilled and Unaware of It”, where Dunning and Kruger detailed that low performers believed they performed far better than they actually had, relative to other participants, even after being shown correct answers (for the study, a variety of tests were administered, including assessments of logical thinking and grammar). The Valley of Despair seems a scary place from the heights of Mount Stupid, but with the Slope of Enlightenment ahead, it’s not so bad.

The almost paradoxical solution to these problems is simple improvement. The issue then becomes how and why we develop and apply strategies for improving at, well, anything. How does anyone decide to take the plunge into the Valley of Despair, when the confidence of Mount Stupid seems to suit some people just fine? Perhaps it comes with the broadening of one’s perspective. Imagine standing atop Mount Stupid. If your perspective isn’t broad enough, all you will see before you is an endless, echoing chasm. But, if you work to see the Slope of Enlightenment, you can use the opportunity of Mount Stupid as the beginning of a fulfilling and humbling journey, rather than as a permanent home.

In addition to humility, curiosity too burns at the heart of these ideas, and they apply to more than isolated scientific experiments and lemon juice-wearing bank robbers. I wrote earlier that the effects of cognitive biases, and thus of Dunning-Kruger, are ubiquitous, and I cannot stress enough how true that is. Even in a situation as mundane as a conversation between two people, cognitive biases are running amok, leading one or both of the conversation’s participants to not fully grasp the perspective of the other. I believe we have a duty to fight these inclinations and to work to understand each other more fully, for it is only through developing our differing perspectives that we have come so far as a species. It has taken the efforts of countless minds, each its own world of feeling and thought, to devise, create, and maintain all that we have today, and it will take more of the same to forge into the future. To build that world, we must have the courage to be humble, the drive to be curious, and the good sense to trust each other.